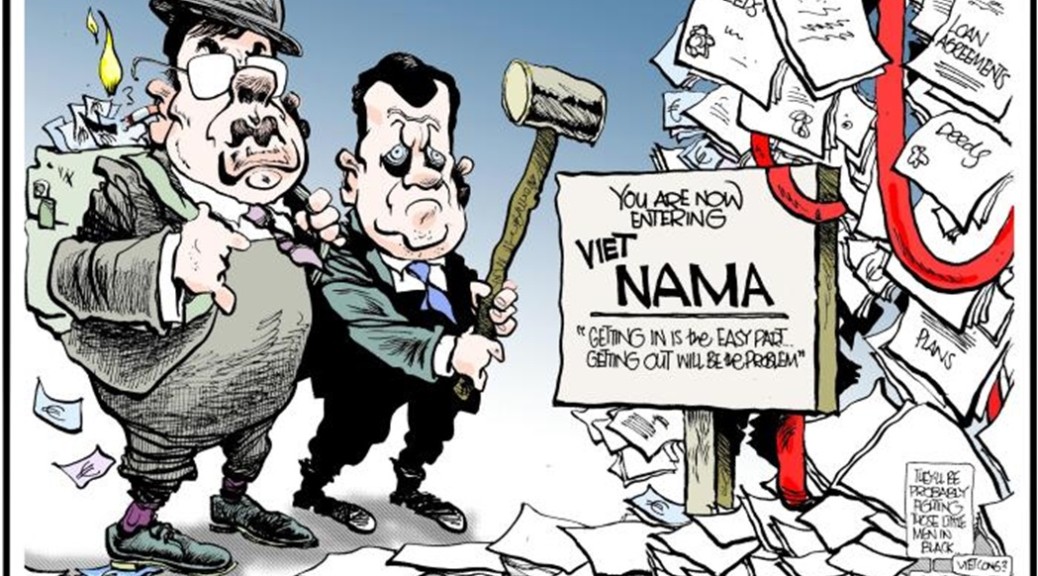

As a recent article published in Property Week discussed, since the passing of The NAMA Act in 2009, many in the property industry have questioned the approach NAMA took in its efforts to restore financial stability and reduce bank debt. The question is, nine years down the line, has the NAMA project been a success.

The approach taken by NAMA toward solving the financial Armageddon caused by banks during the Celtic Tiger era, was seen by many as a drastic and harsh means to create financial stability in Ireland. The objections to the government plan claimed that the creation of a “bad bank” would do nothing to support key government objectives relating to economic recovery. Leo Varadkar, was one such objector, who at the time stated that the creation of NAMA “won’t get credit flowing and it exposes taxpayers to all of the risk.”

By the end of 2011, NAMA had orchestrated over €74bn in loan balance transfers, with only €31.8bn paid in consideration to the banks. In real terms, 57% below market value. Take from that what you will, but within six years, NAMA had already redeemed €30.2bn in senior debts, with the remaining €1.6bn of subordinated debt expected to be cleared by March 2020.

The clerical management of this debt provides a key indication into how NAMA was able to create stability for small business owners during the financial crisis. Irish citizens, with struggling businesses, held loans secured against the value of their homes. As the housing bubble deflated, homes dropped in value – creating uncertainty over repayments. Having purchased their debts, NAMA worked to secure homes for the masses. For many Irish, this meant an end to the way their debt was pursued, as the sale of assets was prioritised based on value. This meant a roof over the heads of the many, and Ireland was able to avoid moral jeopardy without creating wide-spread homelessness. Eventually deals were cut and many were able to keep their homes.

But, while the government owned agency has defied expectation by largely stabilising the Irish economy, scepticism remains as to whether NAMA has been truly successful. Key Irish investors were short-changed by NAMA on many of their projects and the asset ‘flipping’ which would later take place, has left the banks disgruntled by the compulsory purchases. The resultant effect has been that banks have failed to begin lending in the same way as they had pre-crash.

Many, now attribute the current housing supply shortage to the banks reluctance to lend. It is true, bank loans for developers are harder to come by, but there are other financial options out there for investors and developers who understand the market place, such as alternative lenders and private cash reserves. Evidently, there have been winners and losers as far as NAMA is concerned, but as Ireland once again begins to show strong signs of growth, the focus has moved to new tasks. Brexit, one of many new factors for Ireland to consider as it looks to make its mark on the global economy.